The Port of Alexandria

The fish auction begins with the close of 4 a.m. prayers, after the fleet of green-prowled fishing boats dock and unload their catch. Dozens of hawkers barter over wooden crates filled with eels, prawns, crabs, sardines, mullets, and sea bass so recent from the sea their scales glisten and their gills quiver. The stone floor is worn and gleaming from a century of use. Exposed light bulbs dangle from a cat’s cradle of electrical wire below an arched ceiling and the clerestory of a church nave.

I am in a sacred place: the fish market of Alexandria, Egypt’s oldest city and the fountainhead of some of the best seafood in the eastern Mediterranean.

“It’s a good day’s catch,” says Wagih Yusef, who weighs each buyer’s haul from the market’s cast-iron scale. “There’s been strong winds lately and that churns up the fish.”

Wagih has to bellow to make himself heard above the clamor of the bidding and his eyes never deviate from the square counterweight that hovers above the scale. He appears to be in his mid-30s and, like most of the men in the fish market, has been working here his entire life.

A few blocks north is Kadura, a café on the demand side of Alexandria’s most ancient industry. Patrons choose from the day’s catch from ice-filled cartons in a tiled stall no bigger than a walk-in closet. There is al fresco seating on sunny days, with butcher paper for tablecloth and small dishes of the house’s own chili powder. Save for the occasional clang and whir of a tram car passing along Al Ghorfa al Tiganiya Street, Kadura is a primitive but quiet refuge.

Kadura was opened in 1955 by Kadura Abdel Salem. He passed away a little over three years ago, and his sons Mohammed, 25, and Kader, are now running things. They tell the story about how one day, when their father was very young, he and their grandfather went out on a boat that wasn’t much different from the trawlers that bob in the harbor today, though without the diesel-powered engines, electronic navigation devices and power winches. There was a huge storm and the boat almost capsized and when they finally returned safely to shore, Abdel Salam was forbidden by his father from ever fishing again.

Instead, when he was 19 years old, Abdel Salem opened a café with some tables and wicker chairs he had bought for 8 piasters each. Soon, he was hosting Alexandria’s governor and his aides for lunch and during the summer the ministers came from Cairo for Kadura’s signature calamari. Within a few years he opened a restaurant that fronted the sea until the municipality reclaimed a strip of land along the coastline.

Back then, say Alexandrians old enough to remember, the fisherman would tether their boats to the windowpanes of apartment buildings.

* * *

On a recent visit to the city, I met Dr. Galal Araf, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Alexandria, while he was summering with his family at their bungalow at Montazah, a gated beach resort and a former royal compound of the Egyptian monarchy. Dr. Araf, a proud, self-contained man, was seated razor-straight in pleated gabardine trousers and a pressed short-sleeved shirt as he watched his children and grandchildren chat and frolic in the briny Mediterranean air. I asked him about the old days, the twilight time of Alexandria as a City of the World.

“Alexandria,” he told me, his eyes suddenly alight, “was filled with Greeks and Maltese, Italians and Jews. There was a quarter of the city where residents spoke only Greek. People from all over came to Alexandria to see the latest fashions from Europe. Even then, we were rivals to Paris, London, and Rome.”

It’s true that “Alex,” as she is known among her many admirers, has been showing her age. She hasn’t yet recovered from the legacy of Gamal Abdel Nasser, the Egyptian president who in the 1950s nationalized the economy and drove out the Jews and the foreigners. But there is always the harbor, a crescent-shaped setting for a village founded by Alexander the Great and destined to become a pearl. It was the harbor that lured the young Macedonian here in 332 BC, and its bounty has sustained Alexandrians through a turbulent history. Most Middle Eastern cities have gone to seed over the last few generations, but few have slid from such sublimity and none with such grace. Once a flamboyant cosmopolitan with a strong Greek accent, Alex is now Muslim and staid. But even veiled, the old girl can still turn heads.

And in fact, the city is enjoying a mini-renaissance. The library has been reopened as a state-of-the-art temple of multi-media learning and on any given day is filled with student groups, including American ones. Western tourists are rediscovering Alex and some of the old villas, inns, and café’s are getting long-overdue makeovers. Hotels, including the new Four Seasons, are doing a brisk trade hosting international conferences – a testament to the city’s position as an enclave of stability in an otherwise dodgy neighborhood.

Take the Cecil Hotel, for example. Immortalized in Lawrence Durrell’s The Alexandria Quartet as the haunt of libertine expatriates and host to such giants as Somerset Maugham, Henry Moore, and Josephine Baker, the 89-room Cecil has been completely restored. The lobby is an Edwardian rapture, with high ceilings, extravagant crown molding, granite floors polished to the highest sheen, and stately chandeliers. The original elevators, with their intricately tiled parquet floors, have been rehabilitated. Le Jardin, the hotel coffee shop, is the de rigueur spot for lunching ladies and power-espresso breaks; from a window table you can enjoy a languid, if somewhat pricey, lunch in the reflection of a sparkling sea and the city’s iconic horse-drawn carriages clopping along the corniche.

From a perch like that, it’s easy to see how Alexandrians can cling to the conceit that they are more cultivated and urbane than their counterparts in noisy, congested Cairo. As Mountolive, Alexandria Quartet’s debonair but ill-fated diplomat remarks, “Alexandria is still Europe, not the Egypt of rags and sores.”

* * *

An Alexandrian Pâtisseire

I first visited Alexandria nearly a decade ago to write about the re-opening of its famous library, the centerpiece of its restoration drive. But it was the city’s crumbling beauty that hooked me. If Alexandria was Norma Desmond, the aging screen goddess in Sunset Boulevard, I was Joe Gillis, the frustrated writer (minus, sadly, William Holden’s rakish smile and heroically cleft chin) who succumbs to her charms. Constantine Cavafy, the renown Greek poet and one of Alexandria’s most distinguished residents, wrote of Alexandria as a diminishing jewel. Strolling along Alex’s corniche, you can almost hear her reply with a riff off Norma’s classic rejoinder:

I’m STILL big. It’s civilization that got small.

Things Greek – the food, the empire, Cavafy’s verses – and Alexandria’s golden age inhabit one another like old lovers. From its founding until only a few decades ago, Alexandria was a Greek city. Half its population was Greek and Greeks dominated the economy and culture. And while greatly diminished in size, those that remain are defiantly holding on. They congregate each night at the Greek Club on the community’s vast compound of neo-classical schools, community centers, gymnasium, and theatres. The buildings, radiant in faded pastels, date back to the late 19th century and the grounds are immaculately groomed with date palms, citrus trees, and hedgerows. The club itself is unexceptional – just a dozen tables and a bar tended by the Greek-Armenian Aliko, who quietly fills members’ glasses from their personal bottles of scotch that are kept at the bar. Johnny Walker Red is the preferred brand, and single-liter bottles of it, their owners’ identified by names jotted on paste-it notes, line the bar shelves like prizes at a shooting gallery. The music – Aliko also spins disks – alternates between Greek pop and old jazz standards.

It is here where I met Maroun Ayac, a Lebanese optician and restaurant owner whose family came to Alexandria from Beirut in 1898. His short-sleeve shirt is opened at the abdomen and his sunglasses are perched high on his head. He is tanned, with several days growth of grizzled beard. In Alexandria, even eye doctors look like old salts.

At 50, Maroun is young enough to remember Alexandria when it sizzled. He rattles off the names of the dozens of nightclubs, all of them now closed, that used to swing until dawn. Sunbathers on Alexandria’s beaches used to rival those of the French Riviera for daring, he says. Today, women and girls swim in their clothes for fear of offending religious conservatives.

There is nothing fin de siècle about the Greek Club, however. “We are the last of the Greek way,” Maroun says. “But we stick together and we know how to live.”

Aliko brings us olives, Greek salad, spanakotyropitakia – small pastries filled with cheese and spinach – and Armenian pastrami. He refills my glass with scotch just as Rosemary Clooney slinks into Come On-A My House.

* * *

Alexandria has been ardently romanced throughout her 1,200 years. After Alexander came Ptolemy, whose lighthouse was one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. In 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte turned Egypt into a French vassal, only to lose it to the British in an epic sea battle off the Alexandrian coast. (There is as much to see beneath the Alexandrian port as there is above it, with its trove of sunken Greek ceramics and sculpture, the ruins of the lighthouse – it was destroyed by an earthquake in the 14th century – and the remains of Bonaparte’s fleet.) Less than a decade later, an Albanian foot soldier named Muhammad Ali emerged as the Ottoman empire’s viceroy in Egypt, and under his brutal but shrewd administration the city became the entrepot of the global cotton industry. The city’s commodities exchange was one of the world’s most heavily traded.

For the next century, Alexandria reigned as the Mediterranean’s most multicultural city. Vibrant diasporas plied the cotton trade and invigorated the place with related commerce – textiles, garments, finance – to complement the city’s eternal communion with the sea. The Greeks ran the restaurants and cafés, the British the bureaucracy (naturally, as they were Egypt’s occupying power until 1945), the Swiss administered the hospitals and nursing facilities, the Armenians owned the gold shops, the Italians designed the buildings, the French ran the bakeries and patisseries, and the Maltese – as Britain’s Ghurkas of the Mediterranean – patrolled the streets.

Alexandria provided sanctuary, and sometimes exile, for royals and heads of state. Egyptian kings, first Fuad and then his son, Faruk, summered in Alexandria’s palatial villas, along with their ministers. Writers and poets like Cavafy, Durrell, and E.M. Forrester thrived off Alex’s Levantine romance and intrigue. Artists, musicians, and couturiers drew inspiration from its kaleidoscope of cultures and mores.

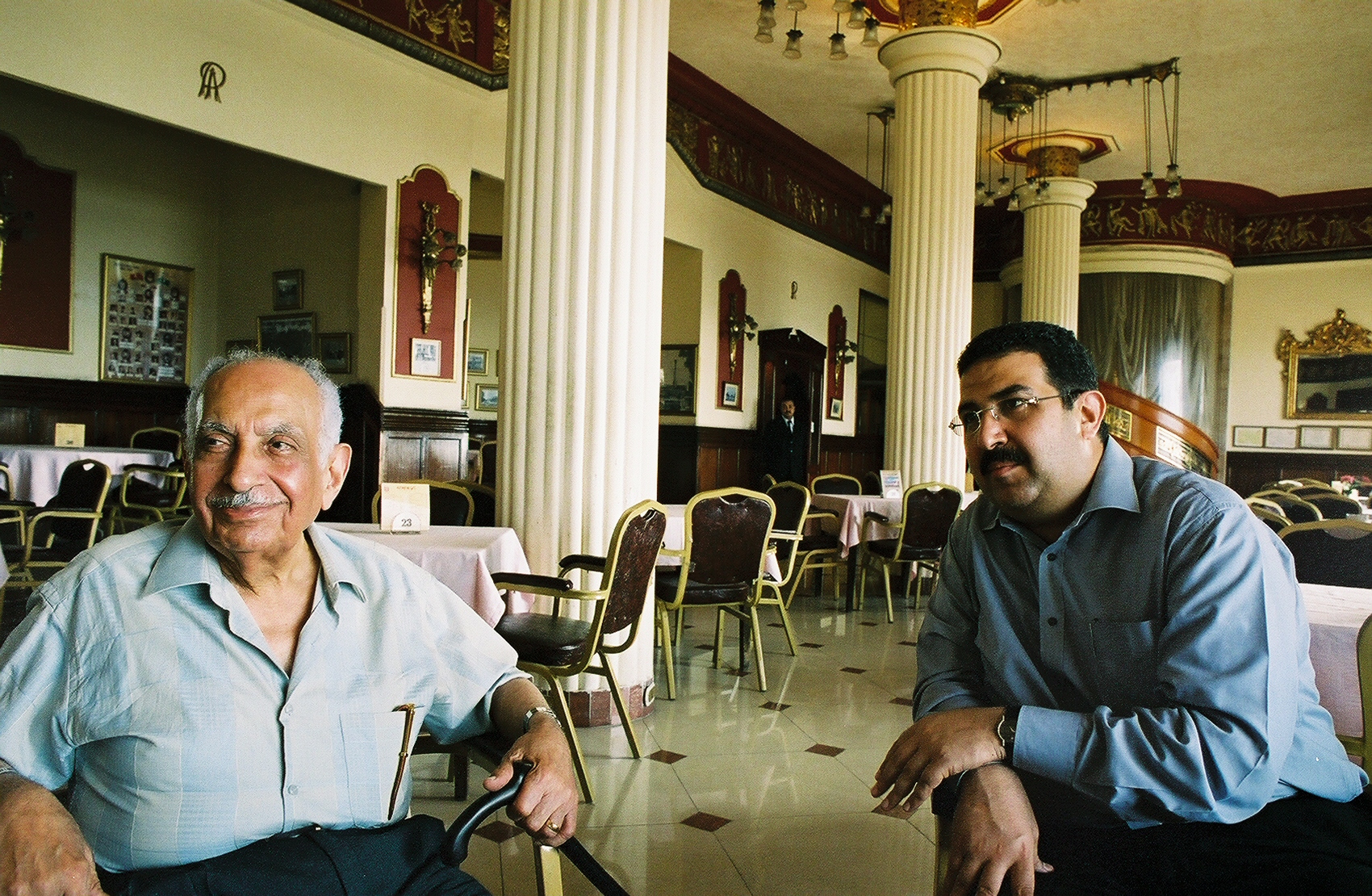

Ahmed and his son Yacoub

Ahmed Nasser was there. He is 87 and, with the help of his son Yacoub, is still owner and proprietor of Athineos, one of Alexandria’s oldest and most popular cafes. At the age of 14, he left his small village to come to Alex. “Every summer,” he told me, “living in Alexandria was like attending a wedding. The king and his cabinet ministers would come here and we’d all be working together, we Muslims, Jews, and Christians, and no one wanted to leave because of the weather and the smell of the sea.”

Then came Gamal Nasser, the Prometheus to Alexandria’s Mt. Olympus, who stole its pyre of light. It was Nasser, they say, who cast the Jews out from Egypt during the Arab-Israeli wars and then seized foreign-owned businesses. Ahmed, a Muslim, bought Athineos in 1968 from the widow of its founder Constantin Athineos after she’d finally had enough and returned to Greece.

Out of respect for Athineos’s founder, Nasser kept the name. In tribute to the past, he and Yacoub have carefully preserved the café as it was the day they bought it 41 years ago, with its grand white columns, polished granite floors, dark-wood wainscoting, and an authentic French patisserie. They’ve even opened a Greek bar in the hopes of luring back the Greeks.

That way, when the world returns for a table with a sea view, it will be as if no one ever left.