Ibn Khaldun, the 14th-century Medieval historian, famously developed a theory of social structures called asabiyya, which translates roughly as ‘solidarity.’ It refers to the unifying complex of culture, language and customs that make tribal societies cohere. Ibn Khaldun warned that unless tribal leaders adapt asabiyya to the challenges of urbanism, it will dilute and their societies will atomize.

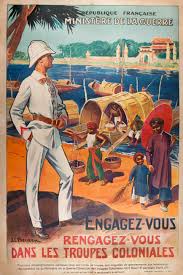

No doubt Ibn Khaldun, who was as good a pundit as he was an historian, economist and sociologist, would be appalled at what stands for Arab leadership today. Since the collapse of the Ottoman empire, Arab potentates have presumed to lead a people for whom they have had a generally low regard and with whom they had little in common. The Anglo-French monarchies imposed on the post-partition Middle East were, with the exception of Faisal I of Iraq, aloof and incompetent. The liberal nationalists who followed were effete colonials who lacked the finesse needed to reconcile the region’s tribal and urban constituencies. Their Baath Party successors were ruthless and atavistic enough to rule effectively but they were suckered into forlorn military adventures - Syria’s Hafez Al-Assad against Israel in 1973, Saddam Hussein in Kuwait - that undid them. Political Islam came and went, thanks to the Muslim Brotherhood’s startling inept performance in Egypt during its first and bloodily abbreviated term in office.

Only Gamal Abdel Nasser, the Egyptian strongman who galvanized the Arab world a half-century ago, earned a popular mandate to lead on a national, if not transnational scale - and he made a hash of it. Since the Arab revolt against despotic rule erupted three years ago, only Tunisia, with its enlightened blend of liberal, ecumenical governance, has survived the mayhem that now consumes the Middle East.

To be fair, the Arabs were never going to cultivate the leadership they deserved so long as the region’s power broker, the United States, subordinated their interests to those of its ally, Israel. That is the price Egyptians and Jordanians pay for peace with their powerful neighbor. And it is a burden shouldered by the Palestinians with no peace, let alone a state, to show for it. Instead they have labored for the last generation with Marwan Barghouti, one of their sharpest political minds and charismatic leaders, wallowing away in Israel’s Hadarim Prison.

Barghouti, 54, is serving a life sentence for the murders of five civilians, crimes for which he denies involvement. As U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry struggles to weave a proposed peace agreement that both Israelis and Palestinians might not categorically reject, Barghouti stands as a flesh-and-blood metaphor for Palestinian statehood: a promise ripe for redemption, still interred. Even behind bars, polls show he would win a “national” election hands down against Islamist as well as secular rivals. According to a 2012 survey, 60% of Palestinians would vote for him for president of the Palestinian Authority if they were given that chance, and he would prevail over both Mahmoud Abbas, the current president of the Palestinian Authority, and Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh.

Pledges by Israeli leaders to release Barghouti as a goodwill gesture - most prominently Shimon Peres’ promise to do so in 2007 - come and go. “If Israel had wanted an agreement with the Palestinians it would have released him from prison by now,” declared Haaretz, Israel’s most respected daily newspaper and the conscience of what remains of the country’s pro-peace wing, in a 2012 editorial. “Barghouti is the most authentic [Palestinian] leader and he can lead his people to an agreement.”

Once an aide to the late Yasser Arafat and a senior official in Fatah, Arafat’s political movement, Barghouti was a fervent believer in a negotiated peace with Israel but abandoned the process in response to the relentless expansion of Jewish settlements on Palestinian land. When the Second Intifada erupted in fall 2000, Barghouti emerged as the intellectual and political architect of its operations in the West Bank. He was unapologetically militant and was closely identified with the al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigade and the Tanzim, Fatah’s armed wing, which stunned his pro-peace friends and supporters in Israel.

Barghouti speaks fluent English and Hebrew, the latter of which he learned during earlier stints in Israeli jails, and before his arrest in 2002 he enjoyed bantering with foreign journalists. During the first few months of the Second Intifada, with Palestine and much of the Middle East simmering around him, he was garrulous, unhurried, and rakish in his trademark leather jacket and well-trimmed moustache.

“The Israelis have revealed themselves to be insincere in their talk of peace,” he told me in early 2001. “They negotiate even as they expand settlements. They leave us no option but to defend ourselves, which is our right.”

There is an indelible image of Barghouti being led into an Israeli courtroom the first day of his trial. He is wearing a brown jumpsuit and his beard has grown out. His hand-cuffed fists are raised over his head and his eyes are defiantly, almost mischievously bright. From that day forward, Barghouti would become the most respected and influential of Palestinian leaders. From his prison cell, where he reads the morning papers in three languages, Barghouti manages to shape Palestinian politics and policy. After breaking with Fatah in 2005, he nearly contested the 2006 vote from jail by forming his own party led by the younger guard of Fatah leaders. Despite polls that showed he would have won an overwhelming share of the popular vote, he backed down at the last minute for the sake of Palestinian unity. The election ended in a victory for Hamas, the Islamist group that refuses to recognize Israel, and Fatah’s bitter rival. The results shocked Israel and the U.S. but came as little surprise to everyone else, and while the election was declared free and fair by monitors, the two allies vowed to isolate and eventually oust Hamas.

In early 2007 I was in the Palestinian territories reporting a story about Mohammad Dahlan, a powerful Arafat protégé who was supported by both the U.S. government and Israel in their covert war against Hamas. After several days of travel through the West Bank and Gaza, it became obvious to me that Barghouti, not Dahlan, represented the future of Palestinian politics. As the Israelis were unlikely to allow me to interview Barghouti himself, I met instead with his wife, Fadwa, a lawyer who serves her husband as counselor, gatekeeper, courier, and spousal confessor. We gathered late one evening over tea in Ramallah, the West Bank’s unofficial capital city. The newspapers that day had led with stories of America’s then-Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice’s latest visit to re-ignite a stalled peace process. Though Fadwa dismissed Rice’s efforts – “marketing ploys,” she called them – rumors that the Israelis might consider swapping Barghouti and dozens of other Palestinians jailed in Israel for a kidnapped Israeli soldier leavened the atmosphere.

“Marwan is in high spirits,” she said. “He is not demoralized and he sees a steady stream of people, including senior Israelis who believe a prisoner exchange is a good idea.”

Fadwa is allowed twice-monthly visitations with her husband. “The whole process is humiliating,” she told me. “We get up very early and meet with members of the Red Cross, then we board a bus with other families of prisoners that takes us through Kalandia [a Palestinian refugee camp along the main Jerusalem-Ramallah road]. The process is so chaotic that family members often abuse each other. It is 20 hours of torture, and then you get 45 minutes with your loved one with a plate of glass running in between and a phone that often doesn’t work and by the time you get it fixed your 45 minutes are up.”

Israeli jails are like political finishing schools for much of the Palestinian leadership, particularly its younger generation. Few within its ranks are held in such high regard as Barghouti, however. Having spent much of his career either in Palestine or in exile in Jordan, he is unassociated with the corruption that soiled Arafat and his inner circle after their own return from exile. Barghouti is fiercely secular but modest in his habits, which makes him popular among the Islamists. As a member of the Nationalist-Islamist Coordination Committee, he brokered a hudna, or temporary truce, with Israel in June 2003 that lasted 152 days – something Fatah leader Mahmoud Abbas was unable to do. He helped draft and ratify the Prisoners Document of May 11, 2006, a compact signed by secular and Islamist Palestinian leaders that was widely regarded as a foundation for a unity government between Hamas and Fatah. It called for a two-state solution and implicit recognition of Israel by Hamas, which agreed to support Abu Mazen, as Abbas is commonly referred to, in his negotiations with Israel.

“Marwan wanted to give Hamas the chance to come closer to Fatah,” Fadwa told me. “He told them if you’re interested in the democratic process, you must compromise. It so happened that many Hamas leaders were in the prison with him, and they would meet during the two hours of exercise they got out of their cells in the morning and the 90 minutes they had in the afternoon. It took them nearly a month to hammer out the pact and then it was circulated to leaders in other prisons. Mazen saw it as the basis for a referendum and gave it his immediate support. Here you have Hamas giving a Fatah leader a mandate to negotiate with Israel, which is something they never gave Arafat.”

Neither the U.S. nor Israel showed any interest in the Prisoners Document. Within six months, fighting broke out in Gaza between Hamas and Fatah. With the Palestinians on the brink of a civil war, Abbas sent an envoy to seek a truce with then-exiled Hamas leader Khaled Mashal in Damascus, but Mashal refused to talk. When Barghouti dispatched Qadura Fares, his long-time ally, to see Mashal, he was welcomed warmly and an agreement was quickly hammered out.

On February 8, 2007, a deal for a Palestinian unity government was struck in Mecca under the imprimatur of Saudi Arabian King Abdullah II. The U.S. and Israel studiously ignored it. In June, fighting resumed in Gaza and Fatah, despite nearly $90 million in U.S. aid to bolster its security forces, was quickly overrun. Dahlan, whom President George W. Bush once described as “our guy” in Gaza, fled. The Gaza strip, needless to say, remains under Hamas’ authority.

Rumors that Barghouti may be freed as a concession by Israel continue to circulate despite Kerry’s flagging efforts for peace. Statesmen from former U.S. secretary of state James Baker to ex-Israeli deputy defense minister Ephraim Sneh have pushed for his release, if nothing else as a counterweight to the still-popular Hamas. Such calls have been ignored by political elites in Washington and Israel who refuse to acknowledge an iron law of Middle Eastern conflict: Arab leadership, once spurned by the West, is inevitably replaced by a more hostile and inflexible one.

In the 1950s, the U.S. government managed to chase Western-oriented, Islamist-hating Arab nationalists like Nasser into the arms of the Soviets and got the Baath Socialist Party in return. It then rejected the Baathists which laid the groundwork for an Islamic revival and the ascent of political Islam. It refused to deal with moderate Islamist leaders like ex-Iranian president Mohammad Khatami, who was succeeded by Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Its attempt to isolate and destroy Hamas have reaped a similarly bitter fruit: this week, the New York Times reported how Hamas is struggling to prevent a new generation of extremists from provoking Israel into launching another Gazan war. The story quoted an Israeli security expert lamenting how “the balance of power in Gaza is changing, and not to a very optimistic direction …. Israel and Hamas both have no interest in escalation, but there are other parties that are playing in the Gaza Strip, other bad guys.”

It is no wonder the average Arab on the average Arab Street believes the U.S. and Israel prefer war to peace. I was in Jerusalem’s Old City when Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh announced his support for the Mecca accord, and the enthusiasm was electric. Surely Washington could not ignore such a compromise, I was told, particularly one so heavily invested in by King Abdullah, America’s close ally. Not only did Washington do just that, it was well into a plan to turn Fatah loose on Hamas with American weaponry, a gambit every bit as foolish as it was irresponsible.

Under Arafat, Israel was often justified for complaining there was no one on the Palestinian side willing to negotiate a lasting peace. Today, as the gymnastic equivocations and cynical demands of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamen Netanyahu make clear, the reverse is true. Matti Steinberg, an adviser to three Shin Bet security service chiefs and a leading authority on the Palestinian national movement, put it well: “When people claim [the Palestinians] are not a partner … this is meant to hide the fact that we are not a partner.”

Free Marwan Barghouti.