You can tell a lot about a country by the way it accounts for its imperial past.

Following World War II, for example, Germany endured a scouring public appraisal of its atrocities while Japan - with U.S. complicity - convinced itself that the worst thing it did during the war was to lose it. Great Britain, which as India’s ex-overlord claims paternity for its railroads, postal service and invention of khaki, refuses to apologize for its brutal crackdown on the Sepoy mutiny of 1857, to say nothing of the 1919 killing of hundreds of civilians in the Punjab city of Amritsar. The United States, meanwhile, prefers to finesse its Victorian-era invasion and occupation of Latin American and Pacific states not as imperialism but destiny - or put another way: lebensraum.

And then there is France.

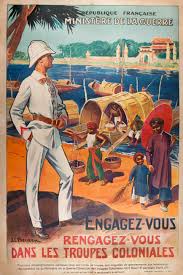

Like most European powers, France celebrated the end of centuries of continental slaughter by subjugating diversely colored people in resource-rich pockets of the world. What began as a global grab for commodities - from sea-otter pelts to pulp and precious metals - was for propaganda’s sake beautified as a mission to redeem foreign unfortunates. Just as Britain had its “White Man’s Burden” so do too did France have its mission civilisatrice, though unlike its more cynical cross-Channel rival France was just arrogant enough to take it seriously. (In this, the French and the Americans have a shared sense of exceptionalism, the lynchpin of their mutual mistrust.)

Last month I visited an exposition of France’s colonial experience in Indochina at the Musée de l’Armée in Paris. Indochine: Des Territoires et des Hommes, 1856-1956, was a fascinating look at how a nation chooses to memorialize its share of an imperial age that helped make the twentieth century the most violent in human history. The exhibit, which closed January 25, began as an overview of the territory itself, curated as a cluster of ancient civilizations exposed to foreign predations by its own civil wars, ethnic rivalries, and warlordism. Earlier settlements by French Jesuits - traditionally the vanguard of worse things to come - were followed by the arrival of French anthropologists, geologists, agronomists and later soldiers and civil servants. The motivation behind Paris’ imperial reach into the region was made clear in the antechamber to the main exhibit hall: to challenge London’s near-monopoly - via the Raj, a land bridge from the Mediterranean to Asia - on the lucrative markets of China.

The objects of war on display revealed the order of battle’s stark asymmetry. The primitive muskets wielded by Vietnamese militias were no match for the aggressor’s highly accurate breech-loading rifles - the Armalites of their era - purchased from American and German arms makers. Sleek, French-made gunships shelled ancient pagodas at will. The closely tailored wool uniforms and pith helmets of French forces, erected ghost-like along with the floridly embroidered gowns of their Vietnamese counterparts, underscored how far European armies had evolved during the Napoleonic wars as Asia dosed under the silken parapet of Chinese vassalage.

The exhibit subtly tempted the visitor onward. Its case against the human costs of empire was all the more profound for its restraint. Post-cards of Japanese prostitutes - “les femmes horizontales” - who worked Saigon’s humid streets in the 1920s and 1930s hung appallingly alongside photos of executed Vietnamese insurrectionists. Newsreels of the 1954 rout of French forces at Dien Bien Phu by Vietnamese communist-nationalist rebels, followed by the failure of the Geneva Conference to pacify the region, hinted at the Americanization of the conflict. Wars of national liberation were by then raging worldwide, a multi-generational process that continues today.

Just ask the French. As curious Parisians and tourists alike filled Indochine‘s exhibit halls France was embroiled militarily in two of its ex-colonies in Africa - Mali and the Central African Republic - and was poised to lead a bombing campaign against Syria, a former French stronghold in the Middle East, before its preemption by Washington. These operations, characterized by President François Hollande as humanitarian missions in conflict-punished states, were authorized with little debate in parliament and accepted with weary resignation by a people who have been in a near-permanent state of war for the last twelve hundred years.

Today, few French believe they have a civilizing mission to play. The once-obscure extreme right, ascendant after decades of unresponsive governance and high unemployment, is bigoted and isolationist while the left busies itself fighting yesterday’s collectivist battles. If there is support for an expansionist foreign policy it is solely as a means to destroy undesirables in their liars rather than fight them on French shores. The Parisian banlieues, suburbs of often shabby public housing, are meanwhile populated with emigrés from the same countries that French troops weredeployed decades ago to subdue. They inhabit an imperial twilight, estranged from Paris as citizens no less then they were as subjects under its hegemony.